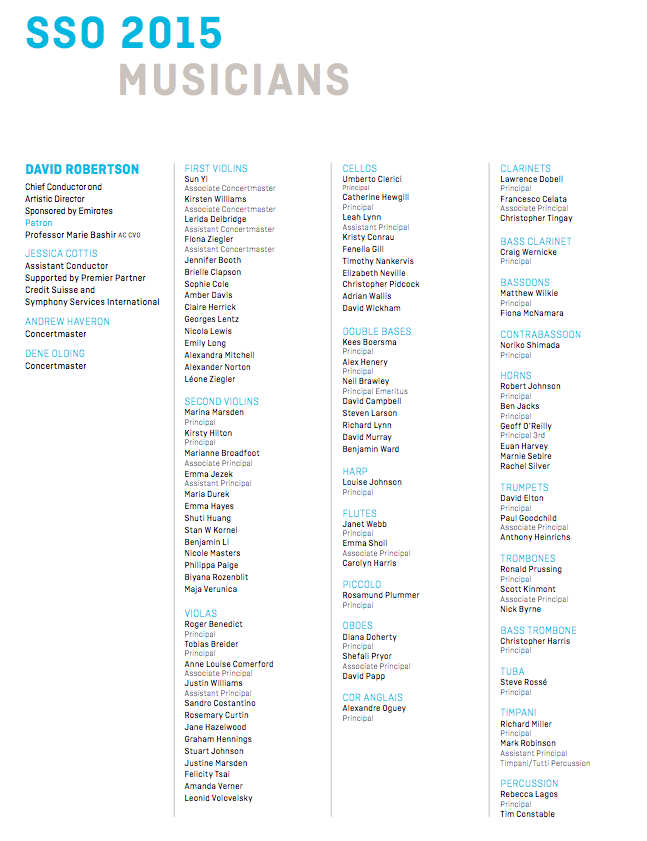

The Sydney Symphony Orchestra employs around 97 musicians on a full-time basis. Above we can see the 2015 cohort, according to the SSO’s 2015 Annual Report. In addition to chief conductor David Robertson and several concert masters, there are around two score string players, two dozen brass and woodwind players, and a percussion section. The SSO obviously also pays guest artists such as sopranos and pianists.

In other words, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra is a very important provider of salaried jobs for artists. This is an economic difficulty for the orchestra, because musicians’ wages are a significant cost. But it is a wonderful outcome for the musicians employed, who have steady jobs with salaries paid every fortnight, plus superannuation, sick leave and all the other normal conditions of full-time employment.

There is no comparable organisation that pays writers in this way in Australia. Why not?

The answer, as so often in these discussions, is essentially that it has ever been thus. Like most artists, writers have traditionally been paid as fee-for-service contractors, providing a literary work in return for a fee. For a novel, this is an advance, around $5,000 or less in the current conditions of the Australian publishing industry. For an article online, this is a one-off fee. The going rate is around $100 to $150 an article. Unless they are journalists writing for news publications, writers are almost never formally employed under the definitions of Australian employment law. They therefore are not paid superannuation, and receive no sick leave or other entitlements. Some small streams of copyright royalties do accrue, but these are negligible for the majority. Most writers are simply ABN-holding small businesses. Exposed to ruthless market forces as small traders, they have little pricing power and small recourse to enforce payment on publishers who decide not to pay.

In this, writers are no different to many other artists. In contemporary music, business models are also flexible and precarious. There are essentially no salaried jobs for musicians playing in rock bands or DJing clubs. Instead, musicians are a precariat, paid by the gig, often in cash, with no expectation of ongoing employment. The entire labour market in advanced economies appears to be heading this way. It is no coincidence that one of the synonyms for the precarious new economy of Uber and Fiverr and zero-hours contracts is the “gig economy”, a term explicitly taken from the contemporary music scene.

It doesn’t have to be like this. The labour market conditions for writers (just as the conditions for doctors, politicians and CEOs) are not simply fixed by the natural law of supply and demand. They are the result of conscious decisions made by policymakers and powerful industry figures.

Other models are available. As the example of the symphony orchestra shows, it is possible to imagine a cultural organisation that pays writers appropriately. Australia maintains a number of publicly-funded symphony orchestras that do pay artists. While many Australians may decry arts funding, and some artists are justifiably critical of the current distribution of that funding, I have never heard anyone complain about artists being paid appropriately, except those who decry the very notion of culture itself.

A new organisation that pays writers

It is possible to imagine an organisation that pays Australian writers in an analogous way to a symphony orchestra.

With appropriate resourcing, an organisation could advertise for a series of full-time fellowships for writers at a reasonable wage. Writers could be selected by a panel of respected peers and then employed on 3-year contracts, with superannuation, sick leave and all the rest. In return, we would expect them to write. At the end of their contracts, a progress report would be submitted.

You could take the analogy further. Why shouldn’t the funding organisation provide non-monetary resources, like working space, library access and perhaps even a small budget for things like travel and research? Tools of the trade could be acquired, like laptops and audio recorders for interviews. A disused space in a cheap suburb could be transformed into a hub for literary production.

There is no a priori reason why such an organisation could not be created. Yes, it needs money. But Australia is a very rich country. There are philanthropists, government funding bodies and ordinary citizens who support such organisations in other artforms. Why not literature?

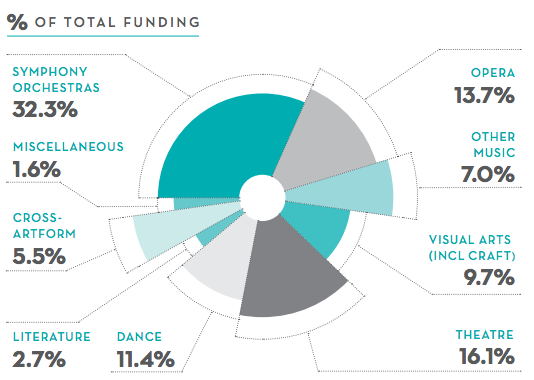

Indeed, on current funding distributions, there is a compelling case to support something like this. Story-telling is at the heart of what makes us human. Narrative is a core aspect of nearly all forms of culture. Reading is the second-most popular form of cultural consumption in Australia, after screen entertainment. But literature receives just 2.7% of Australia Council grant funding. Symphony orchestras receive 32%.

Above: Australia Council funding distribution by artform, 2015-16.

The need for such an organisation is demonstrably great. Before winning the Man Booker, Richard Flanagan considered working in the mining sector. Before she won the Stella and Prime Minister’s Prizes, Charlotte Wood told me in an interview she could not make a living from her fiction. But most writers never win a prize. According to economist David Throsby, the average literary income for writers in 2007-08 was just $11,100, and the median literary income was just $3,600. Both figures were the lowest for all the artforms in Throsby’s survey.

What would it cost?

A modest beginning would see 20 writers funded for 3 year fellowships at a living wage with entitlements. I have calculated this using ABS data for the average annual full-time wage in the arts and recreation services industries. In November 2016 this figure was $42,026. Including super, this equates to a total package of $46,018 a year. It would hardly be luxury. But you might pay the rent.

Paying 20 writers this amount costs around $920,000 a year, or rather less than the marketing budget of many large performing arts organisations (Opera Australia’s marketing budget was $10.7m in 2015). Even if we assume that an office must be kept and a part-time administrator and book keeper must be paid, plus some ancillary costs, it seems reasonable to assume the whole thing could be done for not much more than $1 million a year. Paying 20 writers for 3 years would come out to a bit more than $3 million.

The model has the advantage of being highly scalable. As more funding becomes available, more fellowships could be offered.

By way of comparison, in 2015, the federal government took $6 million over three years from the Australia Council for the purposes of setting up a new body for the literature sector in the form of a Books Council. The government changed its mind, however, pulling the funding before the Council even formed. The money disappeared from the Australia Council’s budget — just another of the many insults and injuries inflicted on the agency by the Coalition since 2013. In other words, there is certainly federal funding available, and there is a strong case for the government to return funding expressly promised to the literature sector.

Who would fund it?

As argued above, there is a strong case for federal funding from the taxpayer. But this project is small, scalable and easily fundable through philanthropic means. Once up and running, it could well attract considerable support in the form of micro-philanthropy and crowd-funding. It is certainly feasible that paid subscriptions or memberships could be issued. A series of talks and workshops could also generate own-source income, although these have their own costs and should be carefully constrained so as not to overtake the primary purpose of the organisation.

The obvious needs to be spelt out: this is not a for-profit business model, and should never be confused for one. The goal of the organisation should be to pay writers, not to reach some mythical state of “sustainability”.

How it would work

We are basically talking about setting up a small-to-medium arts organisation to pay writers living wages. There is a strong sector of such cultural organisations in Australia already, delivering impressive returns on government investment in the form of cultural production and audience reach.

A lean organisation would consist of a board of eminent authors, editors and publishers, with the requisite directors enjoying business, legal and accounting experience. A fully fledged staff is probably not necessary to begin with, and the company could get by with a project officer to administer day-to-day activities, with appropriate part-time help in the form of book keeping, back office, a website and so on. Small arts organisations are incredibly lean beasts, and can be run very efficiently. As the organisation grows, it could eventually hire a skeleton staff to leverage the organisation’s reach, such as a development manager, marketer, and extra project officers as necessary.

Fellowships would be advertised for nationally; there would be considerable interest. The majority of fellowships should go to mid-career and established writers, but some should be reserved for young and emerging writers. Diversity should be a key criterion, with specific targets such as gender parity and appropriate representation of minorities. There should be a mix of fiction, non-fiction, writing for the stage, and poetry. Applications should be short and the process should be simple and transparent.

Successful applicants would be asked to focus on long and ambitious projects that a period of stable employment could support. This doesn’t need to be a big book: it could, for instance, take the form of a series of essays, a number of poetry collections, or the sustained pursuit of short-form criticism.

Fellowships should be acquitted quite simply: in short reports penned annually, with a longer report submitted on completion. Publication outcomes, international markets reached, and prizes won would soon demonstrate impressive results for the metrically minded.

Why do it?

To reiterate, the idea is to pay a number of writers a stable wage. Unlike the lotteries of literary prizes, grants or advances, fellowships offer stable income. Writers would be paid fortnightly for three years. They would be able to pay the rent, buy food, and to save for a mortgage or for old age.

Proponents of culture tend to assume that art is a simple and unadulterated social good, and that more of it is better. You need not believe that to support this proposal. You need only ask whether a mature and diverse democracy would benefit from the ongoing employment of professional story-tellers. In a world that grows ever more complex, the need for sensitive interpretation of the interior lives of our fellow citizens has never been greater.

The extrinsic benefits to Australia of fostering such understanding will be very large. The mere fact that such an organisation exists will also engender huge goodwill. The knowledge that important writers are being supported will quickly give tens of thousands of Australian readers immense pleasure and pride.

But the real reason to do it is simpler even than that. Literature is a good in and of itself. The telling of stories is a fundamental human need. As I argued in my book last year, culture is central to who we are as modern Australians. Supporting it is good for our democracy and our society, because literature enriches not merely separate individuals, but the common good.

You must be logged in to post a comment.